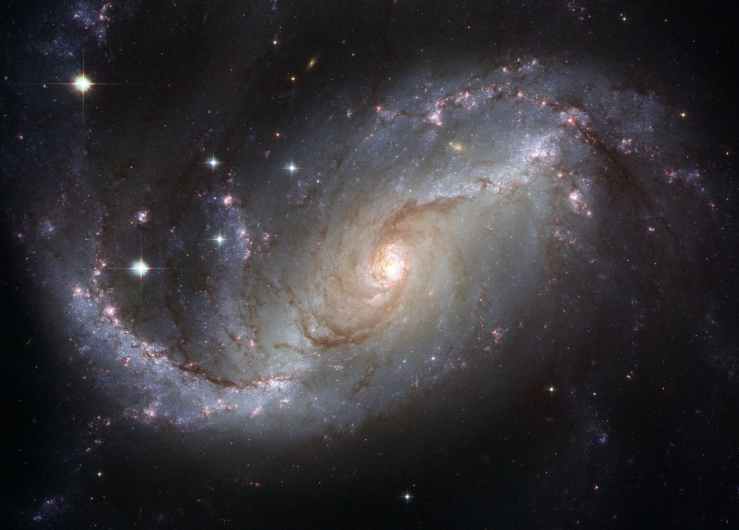

When we have a theory about something, it’s essentially an understanding of how we believe something is supposed to work, or what its true nature is. It’s like an organized system with a network of branches that connect to different parts that permeate from larger categories to smaller ones in a harmonic way. These categories help to explain, what seem to be, random and unorganized events, using a methodical and holistic approach. In other words, a theory is supposed to be a predicator of varying events/outcomes using an algorithm like a flow chart, or a system of unbroken links like a mind map. When those predictions are verified repeatedly across different situations and or environments, the theory itself becomes more grounded, more real, until it becomes so undistinguishable from reality that it evolves into a formula or a scientific law, rather than just a strong conviction we have.

But a theory has to start from somewhere. It starts off as a question, which evolves into a hypothesis, because as we encounter events that are, on the surface, random and causeless, we try to rationalize and answer the “why” to know and understand what’s happening around us and in the world. But a theory can collapse if it doesn’t align with the predicted outcomes–the world–or with what it’s trying to explain. When that happens, we have to go back to the drawing board and see what didn’t work, why it didn’t stand up to the truth.

In the realm of science, the checks and balances of verifying theories is clearcut, because there are practical consequences if the laws of nature aren’t obeyed, or if the wrong processes or materials are used in the construction of structures or products, such as cars, buildings, airplanes, roads, bridges, etc. A car won’t operate, a building won’t stand, an airplane won’t take off, a road will crack or cave in, and bridges won’t stay up for long if the laws of nature are contradicted or if the materials or if the construction process is faulty.

But in our own lives, affirming or denying a theory is a bit more tricky. Although a theory will play out it in our choices and in their results, it’s up to us as to analyze it, modify it, and ultimately, to decide whether to keep or discard said theory. Furthermore, a theory could be interpreted differently from person to person based on how that theory interacts with the other theories they already hold, in addition to its compatibility with them.

Unlike the realm of science, the social realm is much more dynamic, since it involves people and the complex interaction of their choices with others given everyones’ experiences and values. We can read books and theorize about human psychology and human behavior to approximate what people’s choices will be. The same could be said regarding theories about how to go about achieving success or to be happy. But even if two or more people hold the same theory, it can play out differently for them, since the world is invariably complex, and often times, mysterious. That’s why we ponder after a life changing event, if it was chance, coincidence, luck, destiny, or the divine that caused it. And given that gray area of the unknown, a theory is more like a framework, a guide, since life isn’t just a theory, but an experience that has to be lived in order for us to grow from it.